Middle Ages

1. The advent of Christianity and the arrival of Norsemen

The mission of St.Willibrord

In 717, the Northumbrian missionary Willibrord visited Pharos on a Carolingian-sponsored mission with the express purpose of trying to convert the pagan inhabitants living there. His mission was organized in the hope that, once the islanders had converted to Christianity, the Franks could gain control of the important trade port of Victoria, which they had up to that point been unable to do. He was swiftly expelled from the kingdom of Nobila, and ended up preaching in the least inhabited areas of Aurora and Solaria, having set his base in today's St.Willibrodus. He was very successful, founding influential missions and Christian seminaries in Eden, St.Michiel, Sacralia and Egmondchurch, while his presence inspired the small pre-existing communities of Christians in the kingdom to unite and reorganize. Although proselytization was avoided in Nobila because of the strict relevant Nobilite policies, Christianity gained significant momentum in Centralia. This first attempt at conversion to Christianity ended abruptly when Willibrord was recalled by Charles Martel in 719, leaving his missions as a significant source of religious influence in their respective pagan areas.

In 717, the Northumbrian missionary Willibrord visited Pharos on a Carolingian-sponsored mission with the express purpose of trying to convert the pagan inhabitants living there. His mission was organized in the hope that, once the islanders had converted to Christianity, the Franks could gain control of the important trade port of Victoria, which they had up to that point been unable to do. He was swiftly expelled from the kingdom of Nobila, and ended up preaching in the least inhabited areas of Aurora and Solaria, having set his base in today's St.Willibrodus. He was very successful, founding influential missions and Christian seminaries in Eden, St.Michiel, Sacralia and Egmondchurch, while his presence inspired the small pre-existing communities of Christians in the kingdom to unite and reorganize. Although proselytization was avoided in Nobila because of the strict relevant Nobilite policies, Christianity gained significant momentum in Centralia. This first attempt at conversion to Christianity ended abruptly when Willibrord was recalled by Charles Martel in 719, leaving his missions as a significant source of religious influence in their respective pagan areas.

The next missionaries that visited Pharos were members of a Hiberno-Scottish mission or hermits, known as Papar, who also came in the 8th century. Although no archaeological discoveries indicate the extent of their travelling, it was described in reports in Britain. Their absence from the island's records is attributed to the fact that they seemingly were not in touch with the Greek population, as they concentrated on the islands many Celts inhabiting Solaria, whom they seem to have converted to Christianity en masse. The monks are supposed to have left with the arrival of Norsemen, who systematically settled in the period circa 870-930.

The invasion of the Norsemen

By the end of the 9th century the Norsemen had shifted their attention and efforts from plundering to invasion, mainly due to the overpopulation of Scandinavia, which strained resources and arable land. The first known permanent Norse settler was Elisdur Gellerson, who built his homestead in Helsinborg in the year 874. Gellerson was followed by many other emigrant settlers, largely Norsemen and their Irish serfs. By 930, most land in Solaria had been claimed and the Norsemen started pushing southwards. After the destruction of Satea, the Diacrian Alliance city-states reached an understanding with the advancing Norsemen, offering their support in return for being left unharmed - indeed no further major incidents occurred in Diacria or Aurora. Satea was renamed Satemberg and became the administrative center of Norsemen in the region.

By the end of the 9th century the Norsemen had shifted their attention and efforts from plundering to invasion, mainly due to the overpopulation of Scandinavia, which strained resources and arable land. The first known permanent Norse settler was Elisdur Gellerson, who built his homestead in Helsinborg in the year 874. Gellerson was followed by many other emigrant settlers, largely Norsemen and their Irish serfs. By 930, most land in Solaria had been claimed and the Norsemen started pushing southwards. After the destruction of Satea, the Diacrian Alliance city-states reached an understanding with the advancing Norsemen, offering their support in return for being left unharmed - indeed no further major incidents occurred in Diacria or Aurora. Satea was renamed Satemberg and became the administrative center of Norsemen in the region.

The efforts of the kingdom of Nobila to resist the advancing Norsemen was hampered by the desertion of Sorvykon and Victoria, who reached an agreement with the invaders, similar to that of the Diacrian Alliance. Centropolis and Scandia were razed to the ground, before the Burger Revolution of 956 ended the monarchy in Nobila, resistance to the Norse and, consequently, the war. The Norsemen established additional peripheral centers in Schottegut, Trandor, and Holborn, through which they were able to maintain peace and stability in their domain. By now, they occupied directly Solaria, Daisland and Centralia, with Diacrian and Auroran cities as vassal states.

2. The Sip Lyg (Pharonian Commonwealth) and Norwegian encroachment

The Pharonian Commonwealth

Despite their conquests, the Norsemen were quick to recognize that the situation was untenable in the long run, as they represented a small minority in the island and the various ethnicities could easily overtake them if they would revolt. They strived to follow more inclusive policies by introducing in 978 the Sip Lyg, a legislative and judiciary parliament, which was founded as the political hub of the so-called Pharonian Commonwealth at Hilvar. This parliament included representatives from all major areas and was taking decision in matters of internal feuds and land rights. The representatives were internally allied according to the origin of their city's settlers, but the Norse delegation had a veto over all major decisions.

Despite their conquests, the Norsemen were quick to recognize that the situation was untenable in the long run, as they represented a small minority in the island and the various ethnicities could easily overtake them if they would revolt. They strived to follow more inclusive policies by introducing in 978 the Sip Lyg, a legislative and judiciary parliament, which was founded as the political hub of the so-called Pharonian Commonwealth at Hilvar. This parliament included representatives from all major areas and was taking decision in matters of internal feuds and land rights. The representatives were internally allied according to the origin of their city's settlers, but the Norse delegation had a veto over all major decisions.

For nearly 220 years, the arrangement provided a respectable possibility for the cities to voice their opinions and influence the outcome of strives. It was a period of calm and relative prosperity, with commerce and artisanship regaining the lost ground of the war periods. Landowners still held significant power, although they were inferior to the Norse overlords. Pharos, during this era, avoided the expansionism of the Angevin Empire, because of its non-strategic location - being in the outskirts of the known world. Orthodox scholars and missionaries that visited the island from the Byzantine Empire were spectacularly more successful than their Catholic forerunners in spreading the Christian faith, as their Greek origins made them more acceptable to the island's strong and influential communities of Greek descent.

The annexation of Solaria by Norway

In 1194 Harald Maddadsson, Earl of Solaria, supported an invasion of Norway in support of a pretender king. The invading army was beaten in the Battle of Florvåg and Maddadson sailed to Norway In 1195 to reconcile with King Sverre. As punishment, the earldom of Solaria was placed under the direct rule of the Norwegian king. To protest this direct foreign annexation, the representatives of the lands from Deltalene in the north to Victoria in the south reached an agreement (Concordat a Regina) which proclaimed their separate identity from their Norse-occupied neighbors, vowed mutual assistance and abandoned the Commonwealth. Historians agree that this particular act of the leaders of these lands, albeit under the strong influence of Victoria, has indeed led within a few decades to the firm establishment of a distinct identity - serving the political interests of the region's rulers but affirming a reality that was becoming all the more evident in the past few centuries.

Two years later, under the leadership of Sorvykon, the representatives of the lands of South Pharos also withdrew from the Commonwealth, which remained Pharonian only in name, as it was representing only areas under direct or indirect Norse rule. Losing its raison d'être, the Sip Lyg and the Commonwealth were formally dissolved after three more sessions (18 months). Internal strife resumed among the various earldoms and independent states, although initially it took the form of minor skirmishes as all parties were more interested in consolidating control over their own lands rather than expanding their occupation.

3. The Earldoms of Pharos

There were many reasons suggested for the simmering unrest in the island: The absence of a strong central authority favored centrifugal forces and chieftains jumped on any opportunity to acquire more land; Norse security could not be practically enforced in the island's independent South and South-West; the predominance of Norsemen in the Sip Lyg had created ill feelings among Pharonians, especially those aware of a distinct (privileged) identity in the independent powerful Southern Earldoms who objected to the oversight of the King of Norway - a foreigner - on their affairs; internal strife was also in parts caused by the theological differences between Catholics and the more numerous Orthodox Christians, who harbored different ideas regarding the political role of their religious leaders; external influences, especially from the English king Henry II of the House of Plantagenet, stirred dissent among chieftains in South Pharos in an effort to establish privileged zones of influence.

There is a degree of truth in all the proposed reasons but the simpler explanation is that the Norse occupation was insufficiently established to subjugate the existing distinct and strong identities of Pharonians, as these identities had developed over the past millennium. In short, it was impossible to assimilate the island's inhabitants into a new order due to both their strong and diverse cultural history and to the relative weakness of the Norse occupation in this respect.

Over the next 60 years, the most significant development was the rapid conversion of almost all areas of the island into earldoms, in the manner implemented by the Norse in their areas. The organization of these earldoms was more centralized than in any previous political experiment on the island and the first traits of the current organization of the island are easily recognizable.

The Norse consolidated their control over large areas of central and northern Pharos, subjugating the remaining free cities of the former Diacrian Alliance and the Hinji territories. In addition to the Norwegian Jarldømmet (Earldom) of Solaria (Villemstad), they established the independent Norse Earldoms of Diacria (Satemberg), Aurora (Trandor), Daisland (Holborn) and the Store Jarldømmet (Major Earldom) of Schottegut, which ruled over Western Centralia and the Hinji territories. The Earldom of Nobila maintained a nominal independence, albeit one strongly resembling that of a vassal state. The Pharonian Earldoms of Concordia (Victoria) and South Pharos (Sorvykon) maintained a military alliance that permitted them to fight successfully two wars in order to maintain their independence against the Norsemen. By 1263 the obvious stalemate in the battlefields had led to the cessation of hostilities.

The Norse consolidated their control over large areas of central and northern Pharos, subjugating the remaining free cities of the former Diacrian Alliance and the Hinji territories. In addition to the Norwegian Jarldømmet (Earldom) of Solaria (Villemstad), they established the independent Norse Earldoms of Diacria (Satemberg), Aurora (Trandor), Daisland (Holborn) and the Store Jarldømmet (Major Earldom) of Schottegut, which ruled over Western Centralia and the Hinji territories. The Earldom of Nobila maintained a nominal independence, albeit one strongly resembling that of a vassal state. The Pharonian Earldoms of Concordia (Victoria) and South Pharos (Sorvykon) maintained a military alliance that permitted them to fight successfully two wars in order to maintain their independence against the Norsemen. By 1263 the obvious stalemate in the battlefields had led to the cessation of hostilities.

4. The Scottish interest

When Alexander III, king of Scotland, became of age in 1262 he declared his intention of continuing the aggressive policy his father had begun towards the western and northern isles off Scotland. Alexander sent a formal demand to the Norwegian King Haakon Haakonsson. Norway had grown to be a substantial nation with influence in Europe and the potential to be a powerful force in war. With this as background, King Haakon rejected all demands from the Scots. The Norwegians regarded all the islands in the North Sea and Northern Atlantic as part of the Norwegian realm. To add weight to his answer, King Haakon set off from Norway in a fleet which is said to have been the largest ever assembled in Norway. The king made landfall on Arran and, after tiresome diplomatic talks, decided to attack. At the same time a large storm set in, which destroyed several of his ships and kept others from making landfall. The Battle of Largs in October 1263 was not decisive and both parties claimed victory, but the Norwegian king's position was hopeless. He returned to Orkney with a discontented army, where he died of fever. King Magnus Lagabøte broke with his father's expansion policy and started negotiations with Alexander III. In the Treaty of Perth of 1266 he surrendered his furthest Norwegian possessions including the Norse earldoms in Pharos to Scotland in return for a large sum and an annuity. Bit by bit, the various Norse earls in Pharos were politically integrated into the Scottish state.

When Alexander III, king of Scotland, became of age in 1262 he declared his intention of continuing the aggressive policy his father had begun towards the western and northern isles off Scotland. Alexander sent a formal demand to the Norwegian King Haakon Haakonsson. Norway had grown to be a substantial nation with influence in Europe and the potential to be a powerful force in war. With this as background, King Haakon rejected all demands from the Scots. The Norwegians regarded all the islands in the North Sea and Northern Atlantic as part of the Norwegian realm. To add weight to his answer, King Haakon set off from Norway in a fleet which is said to have been the largest ever assembled in Norway. The king made landfall on Arran and, after tiresome diplomatic talks, decided to attack. At the same time a large storm set in, which destroyed several of his ships and kept others from making landfall. The Battle of Largs in October 1263 was not decisive and both parties claimed victory, but the Norwegian king's position was hopeless. He returned to Orkney with a discontented army, where he died of fever. King Magnus Lagabøte broke with his father's expansion policy and started negotiations with Alexander III. In the Treaty of Perth of 1266 he surrendered his furthest Norwegian possessions including the Norse earldoms in Pharos to Scotland in return for a large sum and an annuity. Bit by bit, the various Norse earls in Pharos were politically integrated into the Scottish state.

5. The English involvement

Edward I and the Lords of the Isle

King Alexander III's death in 1286 left the Scottish crown in disarray. To avoid the catastrophe of open warfare between Bruce and Balliol, competitors to the throne, the Guardians called upon Edward I of England to decide between them in a process known as the Great Cause. Edward demanded that his claim of feudal overlordship of Scotland be recognized before he would step in and act as arbiter. The Guardians and the claimants still needed Edward's help, and he did manage to pressure them into accepting his lesser though still important terms. The majority of the competitors and the Guardians acknowledged Edward as the rightful overlord of the earldoms of Pharos, even though they could not provide such acknowledgement for the realm as a whole. The second treaty of Northampton, formally passing suzerainty over the Scottish (formerly Norse) earldoms of Northern Pharos to England was signed in 1292. The five earls, in Villemstad, Satemberg, Trandor, Holborn and Schottegut, maintained the collective designation "Lords of the Isle (Triath Nan Eilean)" a Scottish title of nobility with long historical roots. Edward built several castles in order to dominate over the island earls, but the earldoms remained functionally independent, as they had been throughout the periods when they were nominal vassals of the Kings of Norway or Scotland.

King Alexander III's death in 1286 left the Scottish crown in disarray. To avoid the catastrophe of open warfare between Bruce and Balliol, competitors to the throne, the Guardians called upon Edward I of England to decide between them in a process known as the Great Cause. Edward demanded that his claim of feudal overlordship of Scotland be recognized before he would step in and act as arbiter. The Guardians and the claimants still needed Edward's help, and he did manage to pressure them into accepting his lesser though still important terms. The majority of the competitors and the Guardians acknowledged Edward as the rightful overlord of the earldoms of Pharos, even though they could not provide such acknowledgement for the realm as a whole. The second treaty of Northampton, formally passing suzerainty over the Scottish (formerly Norse) earldoms of Northern Pharos to England was signed in 1292. The five earls, in Villemstad, Satemberg, Trandor, Holborn and Schottegut, maintained the collective designation "Lords of the Isle (Triath Nan Eilean)" a Scottish title of nobility with long historical roots. Edward built several castles in order to dominate over the island earls, but the earldoms remained functionally independent, as they had been throughout the periods when they were nominal vassals of the Kings of Norway or Scotland.

The introduction of the English language

The most lasting contribution of the new state of affairs to Pharonian culture was the introduction of English as the official language. Henceforth all official documents were drafted in English, a practice adopted by Pharonian Earldoms too, although the Pharonian idiom in names, titles and popular culture maintained its strength and was recognized as acceptable. The introduction of English affected most visibly the names of various regions and cities of Greek origin. Daisland was re-spelled Diceland, while the most noted changes in city names were those of Nobila to Nobel, Sorvykon to Sorbyke, Khorton to Cress and Corelia to Corel.

The British and Dutch settlers of 14th century

The Great Famine of 1315-1317 was the reason for a new wave of emigrants reaching Pharos. As millions in northern Europe would die over an extended number of years, British and Dutch emigrants arrived in the island. Their arrival is estimated to have increased the island's population by at least 50%. Nonetheless, their presence did not substantially challenge the status quo: The Dutch settled mostly in uninhabited areas of Aurora and Northern Hinji, while the British moved away from the English earldoms, into the South-East of the island, where they revitalized the strained economies of the Pharonian Earldoms. The ethnological characteristics of the island's population were, thereafter, substantially altered with a majority of Norse-Celts in the north, Greek-Dutch in the North-West, Greek in the East, Greek-Iberians in Concordia, Greek-British in the South and a mixture of Iberians, Norse, Greeks, Celts and Carthaginians in the Central and the Hinji regions of the island.

6. Henry of Gilbey and the Black Death

In 1330, the Plantagenet king of England Edward III chose to renew the military conflict with the Kingdom of Scotland. In this framework, he repudiated the Treaty of Northampton. Despite this, English sovereignty over the Northern Pharos earldoms would never be practically challenged by the Scots as they were occupied with the mainland English threat. The fiscal pressure on the English kingdom, caused by Edward's expensive alliances in the framework of hundred years' war, led him in 1340 to default on England's external debt. This default contributed to the collapse of the Compagnia Sorvykana, his main creditor, a major financial house in Europe and the primary force in the politics of the Earldom of South Pharos. The immediate result was a major crisis in the economy of the earldom which Henry of Gilbey, perhaps the greatest of Edward's captains, exploited. By leading a small force, he overtook the weakened earldom and proclaimed himself Earl of South Pharos. The king acknowledged the title and the earldom, possibly after a generous write-off by the new Earl of his large debt of 900,000 gold florins. The Earl of South Pharos was nonetheless not recognized as one of the Lords of the Isle and his earldom was belonging directly to the English crown.

In 1330, the Plantagenet king of England Edward III chose to renew the military conflict with the Kingdom of Scotland. In this framework, he repudiated the Treaty of Northampton. Despite this, English sovereignty over the Northern Pharos earldoms would never be practically challenged by the Scots as they were occupied with the mainland English threat. The fiscal pressure on the English kingdom, caused by Edward's expensive alliances in the framework of hundred years' war, led him in 1340 to default on England's external debt. This default contributed to the collapse of the Compagnia Sorvykana, his main creditor, a major financial house in Europe and the primary force in the politics of the Earldom of South Pharos. The immediate result was a major crisis in the economy of the earldom which Henry of Gilbey, perhaps the greatest of Edward's captains, exploited. By leading a small force, he overtook the weakened earldom and proclaimed himself Earl of South Pharos. The king acknowledged the title and the earldom, possibly after a generous write-off by the new Earl of his large debt of 900,000 gold florins. The Earl of South Pharos was nonetheless not recognized as one of the Lords of the Isle and his earldom was belonging directly to the English crown.

The Black Death and the civil unrest

In 1348, the Black Death struck Europe with full force, killing a third or more of Pharos' population. This calamity halted all major campaigning in Europe. The great landowners struggled with the shortage of manpower and the resulting inflation in labor cost. Most of the English-controlled earldoms implemented the Ordinance and the Statute of Labourers that were adopted by the English Parliament, in order to fix wages, impose price controls and minimize the mobility and rights of laborers. The plague itself did not lead to a full-scale breakdown of government and society in Pharos, and recovery was remarkably swift. Nonetheless, the Ordinance and the Statute of Labourers were very unpopular with the peasants, who wanted higher wages and better living

In 1348, the Black Death struck Europe with full force, killing a third or more of Pharos' population. This calamity halted all major campaigning in Europe. The great landowners struggled with the shortage of manpower and the resulting inflation in labor cost. Most of the English-controlled earldoms implemented the Ordinance and the Statute of Labourers that were adopted by the English Parliament, in order to fix wages, impose price controls and minimize the mobility and rights of laborers. The plague itself did not lead to a full-scale breakdown of government and society in Pharos, and recovery was remarkably swift. Nonetheless, the Ordinance and the Statute of Labourers were very unpopular with the peasants, who wanted higher wages and better living

standards, and were a contributing factor to subsequent peasant revolts, most notably the Burg Yoti Rebellion of 1381. This was one of a number of popular revolts in late medieval Europe and is a major event in the history of Pharos. The name of the Rebellion's leader, William Haleeki, also known as Guard Billy, is still familiar in popular culture although little is known of him. The revolt later came to be seen as the beginning of the collapse of serfdom in medieval Pharos, although the revolt itself was a failure. It increased awareness in the upper classes of the need for the reform of feudalism in Pharos and the appalling misery felt by the lower classes as a result of their enforced slavery.

7. The Pharonian Parliament and the Byzantines

The Pharonian Parliament

By the middle decades of the 14th century, the English presence in Pharos was perceived to be under threat, mostly due to the dissolution of English laws and customs among members of the English-Pharonian ruling class. English settlers were described as "more Pharonian than the Pharonians themselves", referring to them taking up Pharonian law, custom, costume and language. The Hammerfest statutes were introduced in 1361, trying to prevent this "middle nation", which was neither true English nor Pharonian, by reasserting English culture among the English settlers. While the Statutes were sweeping in scope and aim, the English never had the resources to fully implement them. They were abandoned within two years from introduction, leaving a bitter taste among English settlers. The island continued to gain a primarily Pharonian cultural identity, primarily expressed in its spoken idiom.

By the middle decades of the 14th century, the English presence in Pharos was perceived to be under threat, mostly due to the dissolution of English laws and customs among members of the English-Pharonian ruling class. English settlers were described as "more Pharonian than the Pharonians themselves", referring to them taking up Pharonian law, custom, costume and language. The Hammerfest statutes were introduced in 1361, trying to prevent this "middle nation", which was neither true English nor Pharonian, by reasserting English culture among the English settlers. While the Statutes were sweeping in scope and aim, the English never had the resources to fully implement them. They were abandoned within two years from introduction, leaving a bitter taste among English settlers. The island continued to gain a primarily Pharonian cultural identity, primarily expressed in its spoken idiom.

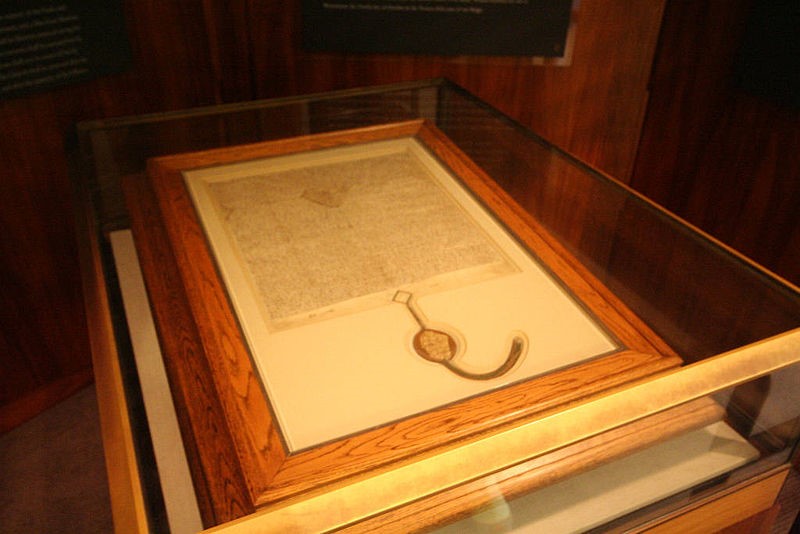

The next 130 years witnessed an acceleration of the ascent of Pharonian society away from English cultural and political domination. In 1397 the Justiciar, Sir Dominic Fan, formally founded, with the king's consent, the Pharonian Parliament in Gilbey Town, the new seat of the Earl of South Pharos. The Parliament was established to represent the Pharonian and English population of the Earldoms of Pharos, based on English laws and practices. It aspired to spread the acceptability of these laws and practices to the ruling classes by providing them with a coherent institutional framework for pursuing their interests. Equally significantly, it was considered a principle condition for extending taxation to the various fieftains - Magna Karta had already been implemented in 1317 in the Great Charter of Pharos. Membership to the Parliament was technically based on fealty to the king, and the preservation of the king's peace. As a result, autonomous Pharonian fieftains, particularly those from Concordia and Nobel, were generally outside of the system, having their own local taxation arrangements. Despite these valiant efforts at assimilation, the 15th century saw shrinking numbers of those loyal to the crown which, along with the growing power of landed families and the increasing inability to carry out judicial rulings, reduced the relevance of the crown's presence in Pharos. The "Pharonian resurgence" was political as well as cultural. Considerable numbers of the Anglo-Pharonian nobility joined the independent Pharonian nobles in asserting their feudal independence. Increasingly, the Pharonian Parliament was being overawed by powerful landed families into passing laws that pursued the agendas

The next 130 years witnessed an acceleration of the ascent of Pharonian society away from English cultural and political domination. In 1397 the Justiciar, Sir Dominic Fan, formally founded, with the king's consent, the Pharonian Parliament in Gilbey Town, the new seat of the Earl of South Pharos. The Parliament was established to represent the Pharonian and English population of the Earldoms of Pharos, based on English laws and practices. It aspired to spread the acceptability of these laws and practices to the ruling classes by providing them with a coherent institutional framework for pursuing their interests. Equally significantly, it was considered a principle condition for extending taxation to the various fieftains - Magna Karta had already been implemented in 1317 in the Great Charter of Pharos. Membership to the Parliament was technically based on fealty to the king, and the preservation of the king's peace. As a result, autonomous Pharonian fieftains, particularly those from Concordia and Nobel, were generally outside of the system, having their own local taxation arrangements. Despite these valiant efforts at assimilation, the 15th century saw shrinking numbers of those loyal to the crown which, along with the growing power of landed families and the increasing inability to carry out judicial rulings, reduced the relevance of the crown's presence in Pharos. The "Pharonian resurgence" was political as well as cultural. Considerable numbers of the Anglo-Pharonian nobility joined the independent Pharonian nobles in asserting their feudal independence. Increasingly, the Pharonian Parliament was being overawed by powerful landed families into passing laws that pursued the agendas

of the different factions in the island. Eventually the crown's actual power shrank to a fortified enclave around Gilbey Town known as the Pal. The English crown was too weak at the time to consider any substantial measures against this indirect insubordination of the various Anglo-Pharonian nobles.

The influence of Byzantines

In the second half of the 15th century, a large number of Byzantine Greeks, fleeing from Constantinople after its fall to the Ottoman Turks, reached the island as they found refuge in the Latin West. They brought with them knowledge and documents from the Greco-Roman tradition that further propelled the Renaissance, which found "fertile soil" in the islands' old Greek tradition and heritage. The major figure among them was Jon Argyr (née Ioannis Argiropoulos) a Greek lecturer, philosopher and humanist, one of the émigré scholars who pioneered the revival of Classical learning in Pharos in the 15th century. He translated Greek philosophical and theological works into Pharonian besides producing rhetorical and theological works in his own. He divided his time between Cress and Eptapolis.

In the second half of the 15th century, a large number of Byzantine Greeks, fleeing from Constantinople after its fall to the Ottoman Turks, reached the island as they found refuge in the Latin West. They brought with them knowledge and documents from the Greco-Roman tradition that further propelled the Renaissance, which found "fertile soil" in the islands' old Greek tradition and heritage. The major figure among them was Jon Argyr (née Ioannis Argiropoulos) a Greek lecturer, philosopher and humanist, one of the émigré scholars who pioneered the revival of Classical learning in Pharos in the 15th century. He translated Greek philosophical and theological works into Pharonian besides producing rhetorical and theological works in his own. He divided his time between Cress and Eptapolis.

It must however be said that the influx of Byzantine Greek scholars into the island had begun much earlier, in the 12th and 13th centuries. Diacria and Diceland were the areas that received most of these Greek refugees, benefiting greatly from their presence, higher culture and expertise. The names of these families are all too familiar to historians as they have supplied significant numbers of administrators and politicians over the next centuries. (The most

significant of the Byzantine-Greek emigrant families were the Votan, Isar, Komnon, Opi, Lekapin, Metxa, Laskar, Aggel, Gavra, Notra, Cores, Tarhan and Dorian. These were of course the families Pharonian transformation -abbreviation- of the original family names).